By Jorge Costa Oliveira

Partner and CEO of JCO Consultancy

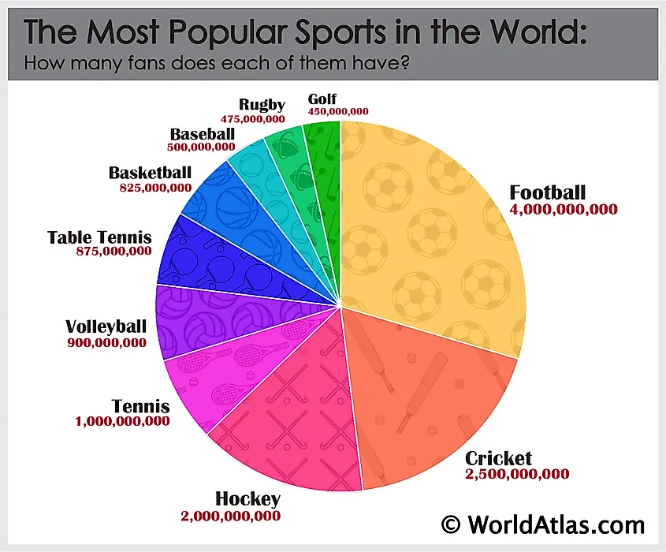

Football (“soccer”, for Americans) is, by far, the most popular sport in the world. It is the most popular spectator sport in the vast majority of the countries worldwide (with relevant exceptions only in North America, South Asia and Oceania) and it is the most popular sport by number of fans (4 billion).

Football reinforced its position as the world’s leading sport with worldwide TV broadcasting. This is particularly true for the main European national professional leagues as well as for international competitions, be them of clubs (the UEFA Champions Cup, the UEFA Europa League) or of national teams (FIFA World Cup and UEFA European Championship and UEFA Nations League). In the second half of the 20th century, football clubs evolved from associations and member owned clubs to corporate structures. The market for investors in European football clubs is characterized by low entry barriers; in contrast to the major sports leagues in the US, there is no artificial limitation of licenses. Moreover, the market for European football club ownership is very diverse. Teams may be, and have been, owned by its members, regional or national businessmen, industrial companies, sports investment firms, financial corporations, other football clubs, or other entities, with no restrictions for foreign investors. In the last two decades, transformation from associations to corporations capable of raising significant funds was undertaken and was the outcome of the significant changes that the business and financial aspects of football underwent as a result of the increasing commercialization of the sport, with clubs generating significant revenue from TV broadcasting rights, merchandising, sponsorship deals, stadium revenue and IPRs, along with a share of the wagering on football sports betting – making this sport-entertainment a multi-billion dollars business. The clubs with more well-known brands received ever growing prize money from the UEFA Champions Cup, bigger TV revenues for premium competitions, and additional funds from the internationalization that the marketing of their famous brands rendered possible. Yet, overall, new waves of investment from several types of investors were generated that facilitated raising ever growing funds needed for clubs in European football leagues. The investors, the financiers and regulatory entities also demanded a proper professional corporate and financial management of the most relevant clubs showing it is possible to make it a profitable business, namely by: (i) monetizing its [international] fan base through streaming, merchandise, and sponsorships; (ii) monetizing its digital footprint through advertisements, partnerships, and merchandise sales; (iii) increasing the club’s revenue streams; (iv) improving the club’s brand value; and (v) managing the club’s financial debt. In the last years, HNWIs, sovereign funds, private equities and other investment funds entered the football arena bringing or raising billions of dollars / euros / pounds. This is a short essay on this phenomenon and its latest background and developments on a quickly changing landscape.

Arabian sovereign investment in football and soft power

In December 2022 Cristiano Ronaldo (CR7) joined Al Nassr in a transaction that may reach 200 million euros / year, while in June 2023 Karim Benzema and N’Golo Kante left Real Madrid and Chelsea, respectively, for Saudi champions Al Ittihad. Al Hilal have recently strengthened its team with Neymar Jr., who the media says will receive 100 million euros / year. Other football stars are expected to continue to enhance the Saudi Professional League (SPL) clubs. This uninterrupted flow of petrodollars comes from the Saudi sovereign wealth fund – the Public Investment Fund (PIF). As part of the Sports Clubs Investment and Privatization Project, four Saudi clubs – Al Ittihad, Al Ahli, Al Nassr and Al Hilal – have been transformed into companies, each of which is owned by PIF (75%) and non-profit foundations. Why is PIF making these multimillion-dollar investments? According to statements by those in charge, in order to increase the value of the club-companies and, subsequently, to sell them, to privatize them. The strategy is not entirely new. Qatar Sports Investments (QSI) – a sub-holding of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund (QIA) investing in sports assets – had already adopted it. Following in the footsteps of Sheikh Mansour [ibn Zayed Al Nahyan] (Prince of Abu Dhabi) who had acquired Manchester City FC in 2008, QSI acquired, in 2011-2012, the French club Paris Saint-Germain FC and, in 2022, took 21.67% of SC Braga, having also invested in the “Premier Padel Tour”, in conjunction with the FIP. On the way, Qatar created (within Al Jazeera) beIN SPORTS and organized, in 2022, the FIFA World Cup.

In parallel, state-owned aviation companies from the UAE and Qatar have also invested heavily in European football; Emirates, Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways all have huge promotion deals with European football clubs worth hundreds of millions of euros.

Inevitably, some accuse the authorities of these GCC countries of sportswashing. Notwithstanding, irrespective of what one calls it – nation branding, sports diplomacy – there is clearly a purpose in the PIF’s strategy: to improve Saudi Arabia’s external image. Another example of this is the investment in Newcastle United, a club in the English Premier League; and PIF has made other international sporting investments – in Formula 1 (Aston Martin), horse racing (Saudi Cup), boxing, tennis, wrestling (WWE) and golf (LIV Golf). For Saudi Arabia’s leadership, sport is one of the pillars of its “Vision 2030” strategy for national development and economic diversification and a vehicle to improve diplomatic relations and gain political goodwill, whilst generating investment in the kingdom and contributing to create new industries and jobs – and the PIF is at the heart of this strategy.

When it comes to football, these signings – and other investments in the sector – facilitate the SPL’s ambitious plan to become one of the top 10 professional leagues in the world by 2030. The signing of so many global football stars will increase the visibility and audiences of the SPL, having already generated deals for television/cable broadcasting in more than 120 countries. In addition to television rights, it will allow various forms of return on investments now made (e.g., via commercial sponsorships, merchandising) as well as strengthening ties with business networks in the West and beyond.

But these investments by Arabian sovereign funds are not motivated only or mainly by a return-on-investment approach. The return most desired by the Saudi, the Emirati and the Qatari leaderships is the strengthening of their soft power at the international level. This is particularly important for the Saudi Arabia leadership, whose goal is to change the image of an ultra-conservative and archaic kingdom where women were not allowed to drive and where music and entertainment were manifestations of the demon, into one of a modern country, stage of mega sporting events, open to tourism and to the outside, leader in futuristic sustainable projects (like NEOM with The Line), with a good quality of life based on a services economy.

Boom in acquisitions in European football by private investment funds

Despite the investments made by [Arabian] sovereign funds in football, the vast majority of investment made in football – and other sports – comes from private investment funds, private equities, other financial entities and HNWIs (hereinafter collectively mentioned as “Funds”). We are going to focus on the Funds taking equity in the corporate structures set up by the clubs.

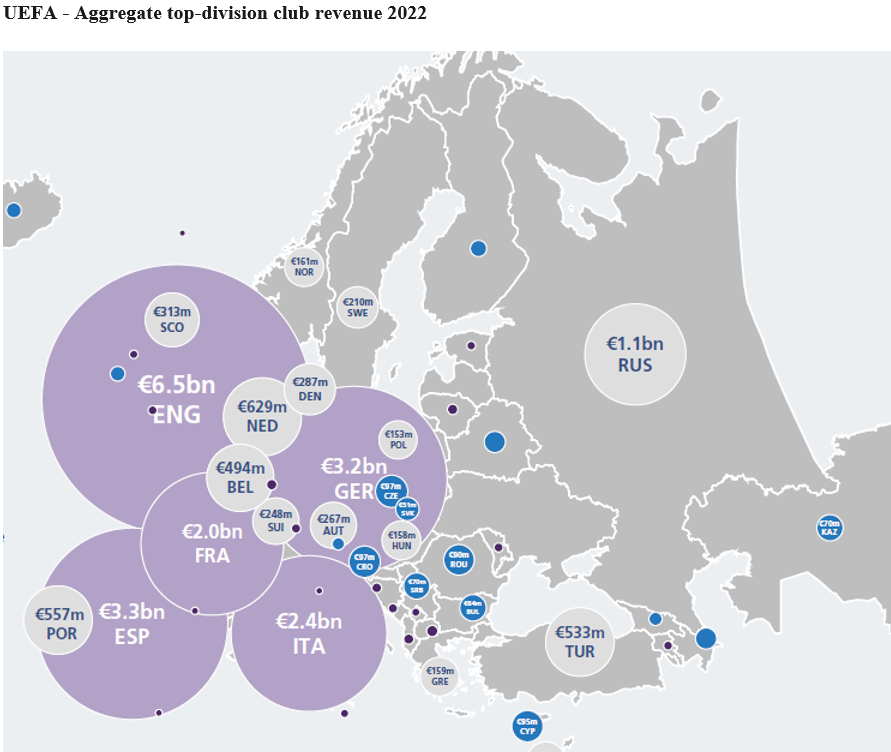

Funds invest with the purpose of making a financial investment on an asset profitable through its sale (or securitization). They expect a good return-on-investment from said sale of the specific asset invested in. In spite of the opinion by some that the European football market (with the exception of England and Germany) has low profitability regardless of escalating revenues, many Funds challenge this view and continue entering the European football market investing in clubs of virtually all leagues. They are also aware that European football clubs typically follow both financial and sporting objectives such as profit or win maximization. However, as per a comprehensive UEFA report, albeit European football revenues have continued to grow, “the financial gaps both between and within leagues are increasing”. There is “a growing concentration of financial resources in the top clubs throughout the leagues in Europe” and “the growth rate of this inequality is increasing”. The monetary muscle of English football clubs was spotlighted in said report, revealing their significant contribution to the European football economy that has soared to an all-time high of 24 billion euros ($25.75 billion) in 2022. The English Premier League’s collective revenue hit a staggering 6.5 billion euros ($7 billion), rivaling the combined income of Spain’s La Liga and Germany’s Bundesliga, which stood around 3.3 billion euros ($3.54 billion) each.

Remarkably, the revenue accrued by the 20 teams of England’s top division equaled the financial intake of all 642 clubs in the remaining 50 European leagues outside the elite “Big Five” leagues (England, Spain, Italy, France, Germany), according to UEFA’s findings. UEFA anticipates that roughly half of the total European football revenue will be claimed by the top 20 money-making clubs, with half of those likely to be from England. However, English clubs were also responsible for a significant portion of the overall pre-tax losses which amounted to 3.2 billion euros ($3.43 billion) across European leagues in 2022.

According to a 2023 UEFA report, the total revenues (broadcasting contracts, commercial partnerships, and gate receipts) of UEFA’s top 55 clubs increased from €11.7 billion in 2009 to €21bn in the 2018 fiscal year. According to a recent KPMG Football Benchmark assessment report of the top European clubs [The European Elite 2023], the aggregate enterprise value (EV) of the 32 most prominent European football clubs increased by 96% in the seven-year period from 2016 to 2023, a performance that far surpasses the FTSE 100 Index. And EV growth is accelerating; in 2023, the aggregate EV of the aforementioned 32 clubs increased to a record value of €51.7 billion (+40% compared to the previous year). Although with a slightly different universe of [20] clubs, the Deloitte Football Money League 2023 report also shows, in 2021/22, increases in total revenue generated of +13% compared to the previous year.

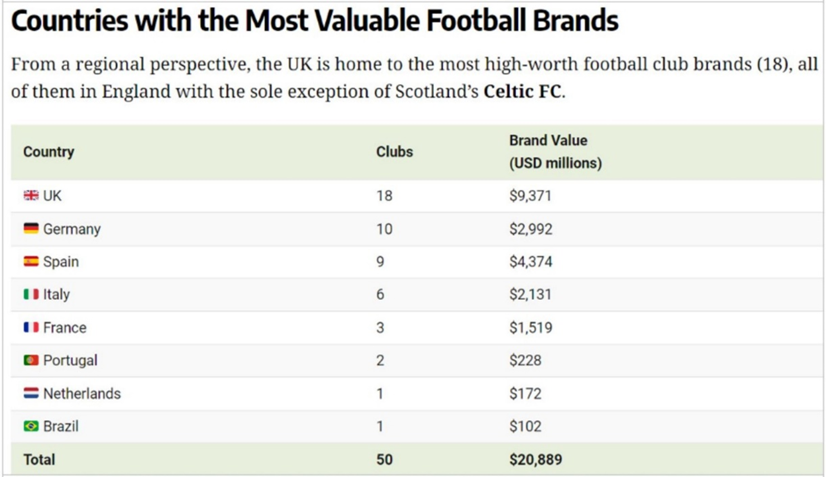

Considering the brand value of the 50 most valuable clubs and listing them by country, there is a huge difference between those of the countries in the 5 “Big Leagues” – United Kingdom (9.371 billion dollars (mM$)), Spain (4.374 billion $), Germany (2.992 billion $), Italy (2.131 billion $) and France (1.519 billion $) – and those of the countries in 6th and 7th place – Portugal (228 M$) and the Netherlands (172 M $).

However, according to UEFA, operating costs increased by 70% in a decade, mainly due to player salaries, that almost doubled (although the introduction of the UEFA Financial Fair Play rules contributed to reduce it). Albeit European football has become profitable in recent years, almost half of top-flight clubs operate at a deficit, resulting in unsustainable business models and in need of capital injections. During the pandemic period, several Funds took the opportunity to buy equity in clubs with upside potential.

Many reports focus on top European clubs from the bigger football leagues, yet some great return-on-investments are made in small teams. A good example is Red Bull’s 2010 investment in fifth-tier side SSV Markranstädt, rebranding it RB Leipzig. Leipzig quickly progressed through the Bundesliga pyramid, earning four promotions in just seven years. In its first year in the Bundesliga, it challenged with Bayern for the title, earning second in the season. Since then, Leipzig won the DFB-Pokal, became Europa League semifinalists, and Champions League semifinalists. RB Leipzig is now valued at €560 million, without counting with the inherent Red Bull brand value appreciation. In the last years, European and American PE – providing non-traditional means of funding – endeavored to identify undervalued small European football clubs with scope to grow in value that need funding and that they consider to be assets with good upside by trimming unnecessary or wasteful expenses, as well as improving operations and reduce inefficiencies. We may see a repetition of the RB Leipzig case in several leagues.

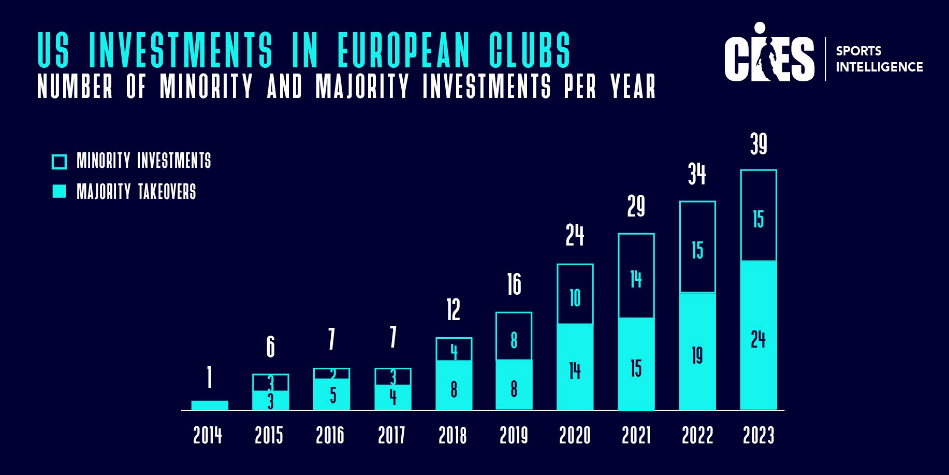

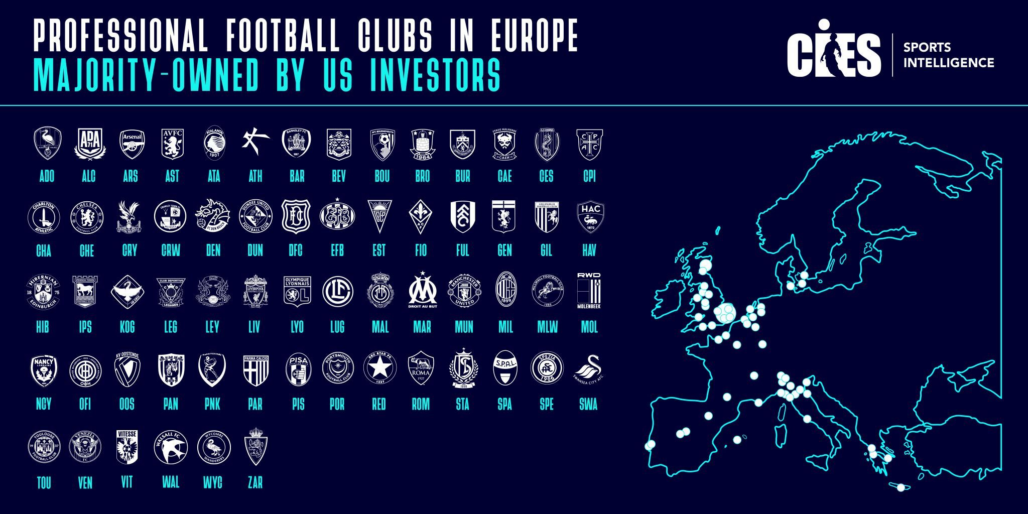

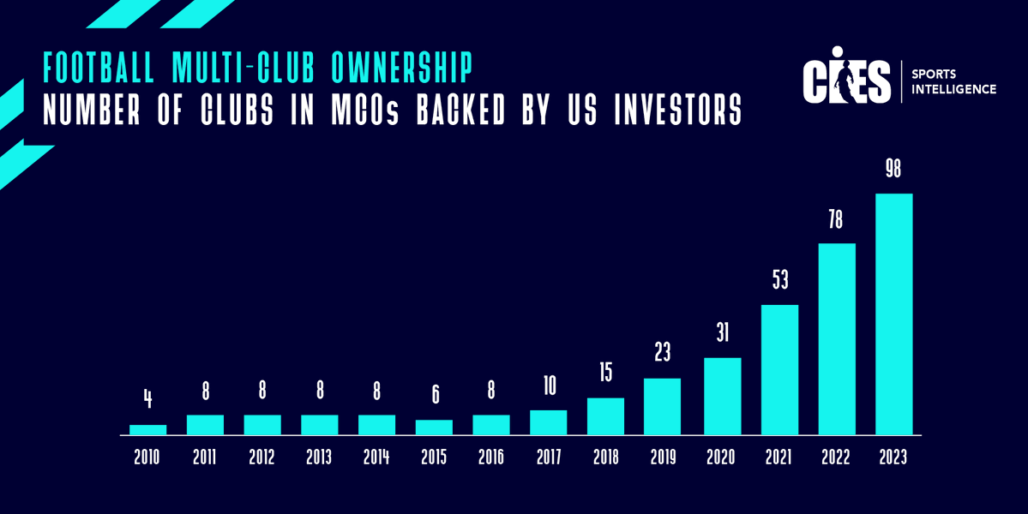

Data shows that the wave of investments from China and South-East Asia that took place in 2016 and 2017 in particular has now nearly stopped and was replaced by an even bigger wave of investments from the US that is currently dominating football M&A in Europe.

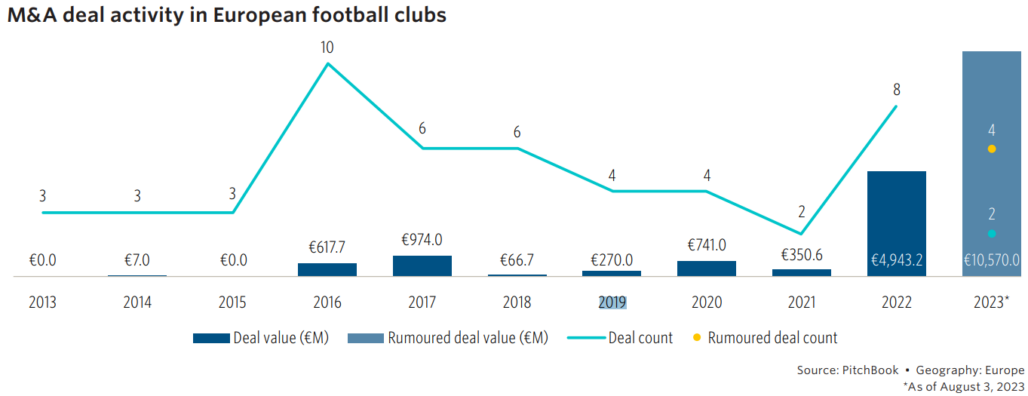

According to a Pitchbook Data report, 35.7% of clubs in the “Big Five” leagues have private equities (PE), venture capital companies or other private investment funds [often using leveraged buyouts (LBO)] in its share capital, many of which are from the US. The strategy of these funds is to promote revenue growth, restructure and better manage clubs and cut unnecessary costs. Restructuring a football club can take several seasons before producing results, with PE operating with return-on-investment expectations of 7 to 10 years. But it must be going well. In 2022 and 2023 an explosion of investments and acquisitions has taken place in these “Big Five” leagues. In 2018 M&A (mergers and acquisitions) in European football did not exceed €66.7 million, compared to €270 million spent in 2019, and €4.9 billion in 2022, with Pitchbook estimating that it would exceed €10.5 billion in 2023.

Multi-club ownership

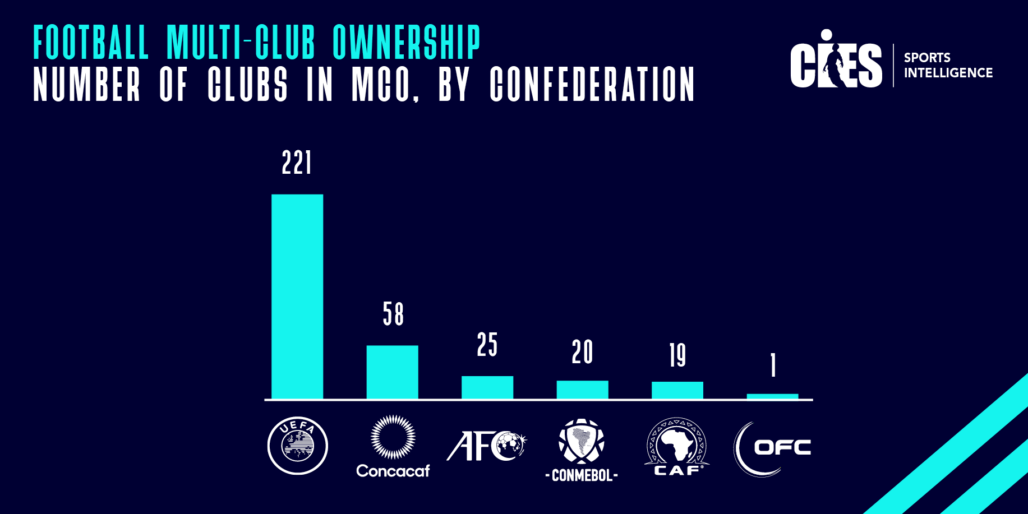

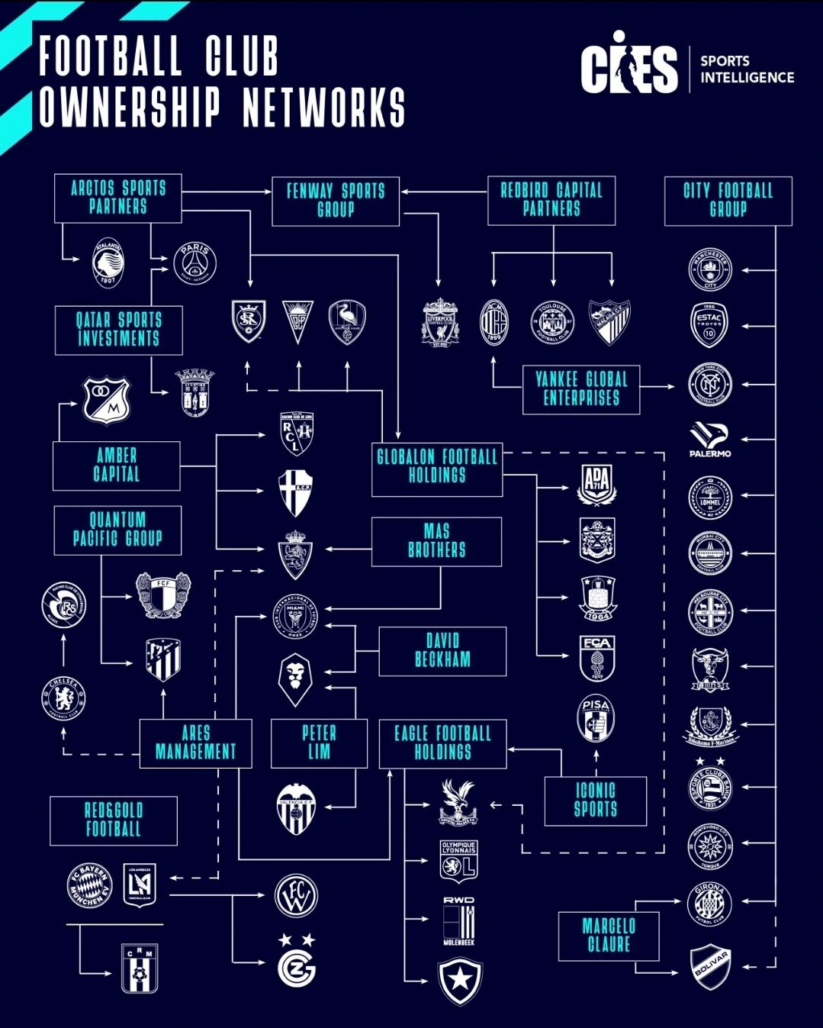

One of the most interesting trends is the creation of small groups of football clubs in different [European and US mostly] countries’ leagues under the same holding corporation controlled by a Fund. Multi-club ownership (MCO) is a business strategy in which one Fund purchases and finances multiple clubs. These various clubs will occasionally be fairly independent, while other times they will be closely bound by a set of explicitly stated principles and practices. MCO is an increasing part of the football landscape, but how many clubs are interlinked across the globe and what are the long-term consequences? In 2017, UEFA’s research found 26 top-flight clubs across Europe involved in cross-ownership. By February 2021, the figure had leapt to 56 teams with 20 investors holding a portfolio of three or more clubs including one in Europe. Overall, UEFA estimated there were then 90 clubs with links and “just under” 50 shareholders owning two or more clubs. By 2021, World Soccer had found 117 clubs controlled by 45 different MCO groups. These clubs were from 37 different countries across the globe, from Egypt to Armenia and the USA, and the largest number (87) were in Europe. CIES Sports Intelligence estimated that, by November 2023, there were 124 entities worldwide which owned two or more football clubs. A November 2023 SportBusiness report, produced in collaboration with CIES Sports Intelligence, found that a total of 301 clubs around the world were part of MCOs; of these, 197 clubs in Europe now belong to a multi-club group. CIES Sports Intelligence reports, on February 2024, that the number is actually nearing 350, of which 221 in Europe (UEFA) and 58 in North & Central America (CONCACAF). The number is certainly going up as these MCO groups keep expanding and more investors are entering this field. Still according to CIES Sports Intelligence, the US (36), England (35) and Spain (30) are the countries with the highest number of clubs in MCO. But the number of clubs involved in MCOs is also growing in other European football leagues.

In some cases, the group controlled by the Fund has clubs in different sports leagues. It is the case of HNWI North American Todd Boehly, who, together with partner Mark Walter, controls Chelsea FC (England) and owns Los Angeles Dodgers (baseball MLB), the Los Angeles Lakers (basketball NBA) and the Los Angeles Sparks (WNBA). It is also the case of the Fenway Sports Group Holdings that controls the Liverpool FC (England), MLB‘s Boston Red Sox, the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins (as well as NASCAR’s RFK Racing and the TMRW Golf League’s Boston Common Golf). Wes Edens co-owns (with Egyptian Nassef Sawiris) Aston Villa FC (England) and is also co-owner of the Milwaukee Bucks NBA franchise and Vitória Guimarães (Portugal, 46%). HNWI North American John Textor controls Crystal Palace FC (England) and also has equity at Olympique Lyonnais (France), Botafogo FR (Brazil), RWD Molenbeek (Belgium) and FC Florida (US). Arsenal FC (England) is owned by the Kroenke Sports & Entertainment, which also owns the Los Angels Rams (NFL), the Denver Nuggets (NBA), the Colorado Avalanche (NHL), the Colorado Rapids (MLS), and the Colorado Mamoth (Lacrosse). Fulham FC (England) is managed by the American Shakid Khan, owner also of the Jacksonville Jaguars (NFL) and of the All Elite Wrestling.

In other cases, the expanding strategy remains focused on football, as is the case of the one being implemented by the City Football Group, that started by owning Manchester City (England) and expanded from there: New York City (2013), Melbourne City (2014), Yokohama F. Marinos (2014, 20%), Montevideo City Torque (2017), Girona FC (2017, 44%), Sichuan Jiniu (2019, 46.7%), Mumbai City FC (2019, 66%), Lommel SK (2020, 99%), Troyes/ESTAC (2020, 100 %), EC Bahia (2022, 90%) and Palermo FC (2022, 94.9%). It also has a partnership with Clube Bolívar (Bolivia).

NewCity Capital, a consortium led by Chien Lee, an Asian-American entrepreneur adept of “Moneyball” strategies, after a successful investment and sale for a record price (in France) of OGC Nice (France), expanded to control Barnsley F.C. (England), FC Thun (Switzerland), K.V. Oostende (Belgium), AS Nancy (France) and Esbjerg fB (Denmark).

777 Partners is a Miami-based Fund that holds controlling stakes at Sevilla FC (Spain), Genoa CFC (Italy), CR Vasco da Gama (Brazil), Melbourne Victory FC (Australia), Standard Liège (Belgium), Red Star FC (France), Hertha BSC (Germany) and Everton FC (England). Italian HNWI Gino Pozzo controls Udinese C (Italy) and Watford FC (England) and, until June 2016, also Granada CF (Spain), when he sold it to the Chinese Jiang Lizhang. He also has a private company of around 30 scouts around the world, which allows him to find players at low cost, many from South America.

In other situations, the strategy seems to be more focused on practical purposes. QSI controls Paris Saint-Germain FC and has a current share of 29% in SC Braga (Portugal) (and will control it if the club’s by-laws are amended to allow it) not only as a good investment in itself, but also as a means to benefit from the current platform that Portuguese clubs have become for South American players into Europe, as well as from Portugal’s good tradition on young players training.

Investment to enhance a Company Brand: the Red Bull case

Another type of investment aimed primarily at improving the image of the investor (and not recouping necessarily a profit directly from the club as an entity) is company branding. In a way, it is the ultimate move of a sponsor; instead of paying an annual contribution to the club, the sponsor takes control [of the management] of the club in order to maximize the image return for its brand. A good example of such a strategy is Red Bull’s investment in football clubs around the world. Red Bull’s stake and influence in four clubs (Red Bull Salzburg, RB Leipzig, Red Bull New York, and Red Bull Brasil), that are part of the firm’s Global Soccer franchise, renders it the ultimate example of a company that invests in football as a way to brand at scale. Despite the success that Red Bull football clubs have experienced, in sportive and commercial terms, the purpose for Red Bull investing in football seems to be to further promote the brand and sell its energy drinks.

Red Bull had previously tapped into branding via sport and had worked out a way to brand at large utilizing extreme sports. Red Bull campaigns focused on associating itself with elite sport, perhaps thus conflating the alleged performance enhancing capabilities of its beverages or at least that its product was trendy and fashionable to drink in the context of sport.

When it came to football, Red Bull followed an ownership strategy rather than a traditional sponsorship method, opening up both the benefits of the ownership over traditional sponsorship models, and, the size, scale and reach of football as opposed to the more niche extreme sports. Branding through football is seen as more covert, as the consumer is less aware that when they watch a branded club in a branded stadium, they are being advertised to.

This path, of investing in football clubs to enhance a company’s brand [at scale], clearly has great upside potential for many brands that want to go beyond the mere sponsorship.

Conclusions

When substantial television broadcasting rights deals became the main source of revenue for European football clubs, Funds realized that, with good management, these clubs could maximize commercial opportunities and generate good returns-on-investment, benefiting from the worldwide visibility of football. The growing prize moneys of the UEFA Champions Cup and the UEFA Europa League created additional interest. The success of initial investments by high-profile investors further catalyzed the Funds appetite for business opportunities in European football clubs, said investment flowing mainly from Europe, China, SE Asia and, lately, the Middle East and the US.

Although no one seems to be investing in this field to lose money, there is a wider diversity of types of investors, that perceive football clubs as a means to achieve different ends. In general terms, investors can be categorized in three groups, according to the main objective pursued:

- Investing for Direct Financial Return: Private Equities.

- Investing for Nation Branding, Soft Power & Sports Diplomacy: UAE, Qatar & Saudi Arabia sovereign funds.

- Investing for Company Branding: Red Bull.

Unlike other industries, the football industry thrives on healthy levels of competition between its participants, whether in terms of a title race, a relegation battle or qualification for UEFA Champions Cup.

In the European football market, financial and sporting objectives remain aligned.

Multi-club ownership keeps growing and international multi-continental groups are multiplying. Funds, in particular Private Equities, are catalyzing it as they find new ways to benefit from the synergies arising from MCO.

In the last years, whether one takes as main criteria the total revenue, the enterprise value or the brand value, the return-on-investment in European football clubs appears to be very good, although most of the information available is centered in the main clubs of the “Big Five” leagues.