China’s dependence on maritime trade is huge – 90% of all Chinese foreign trade, including 80% of its oil and 66% of its LNG imports, but also container and bulk cargo shipments. The vast majority of this foreign trade uses the main sea route between the Far East and Europe – approximately 25%-30% of all global maritime trade passes through the Strait of Malacca – which runs from the ports of China (and Japan, South Korea, Vietnam) to Rotterdam / Istanbul / Athens-Piraeus / Trieste, via the Strait of Malacca, the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean Sea.

The maritime route of China’s BRI

China and Chinese companies – in the last decade under the auspices of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – have invested in the infrastructure along this sea route. First of all, in relevant deep-water ports – some new (e.g. Gwadar, Pakistan; Ream, in Cambodia), some already operating ports (e.g., Hambantota, in Sri Lanka; Athens-Piraeus, Greece); but also in new logistics hubs and access corridors to the hinterland of several countries.

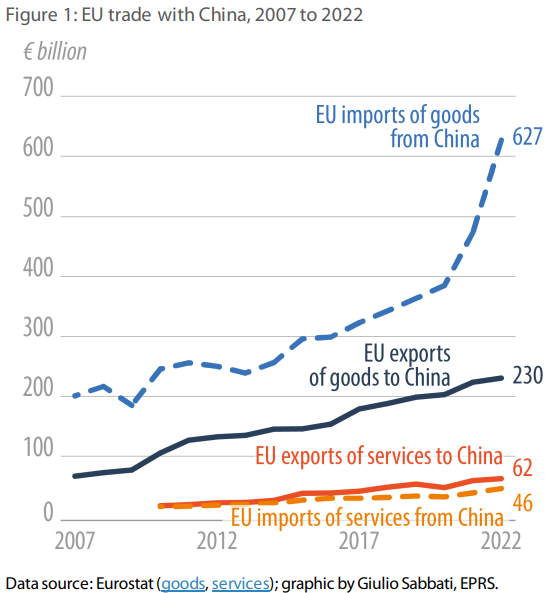

In 2022, the EU exported €230 billion of goods to China and imported €627 billion worth of goods. From 2018 to 2022, China’s trade surplus with the EU increased from €154.7 billion to €396 billion, mainly driven by a strong increase in EU imports (+83%) from China.

China is Europe’s main trading partner for imports of goods, a substantial part of which transits through EU ports, in particular seaports. This is one of the reasons why Chinese companies – in particular China COSCO Shipping Corp and China Merchants Port Holdings – have been taking relevant shareholder positions in strategic port concessionaires in Europe, in particular in Germany (in the holding company of the port of Hamburg, in the multimodal dry port in Duisburg), Belgium (Zeebrugge, a container terminal in Antwerp), Spain (main terminals in Valencia and Bilbao), France (Montoir, Dunkirk, Le Havre and Fos), Greece (Piraeus, Thessaloniki), Italy (Vado Ligure, Naples (sold in the meantime), Palermo?), Malta (Marsaxlokk), The Netherlands (Euromax and Delta terminals in Rotterdam; terminals in Venlo, Amsterdam and Moerdijk), Poland (Gdynia) and Sweden (Stockholm).

According to a study by the University of Antwerp, the sea route via Trieste drastically reduces transport costs. Taking Munich as the destination, the study shows that transport from Shanghai via Trieste takes 33 days, while the route via Rotterdam or Hamburg takes 43 days. From Hong Kong, the southern route reduces transportation to Munich from 37 to 28 days. Hence the interest of Chinese companies in the operation of the port of Trieste. The reduction of transport time means not only greater efficiency in the cost-benefit ratio of maritime transport, but also a reduction in CO2 emissions, since maritime transport is a large and growing source of greenhouse gas emissions.

The “Malacca Dilemma”

The proper functioning of the main current maritime route, via the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal, in any of its variants, depends on its safety. One of the great fears of successive leaderships of the PR China is the vulnerability coined in 2003 by then-president Hu Jintao as the “Malacca Dilemma”, the fear that, in the event of a serious conflict with other powers, especially the US (and also India), a naval blockade will be imposed on products coming to or from China, passing through the Strait of Malacca. This “Malacca Dilemma” has been the subject of special analysis in scenarios of possible war in Taiwan.

The recent attacks on vessels by Houthi rebels at the entrance to the Red Sea reinforce Chinese fears that sooner or later this could be replicated [by terrorists or Islamic fundamentalist groups] in the Strait of Malacca.

To mitigate this fear, China has endeavored to reduce its dependence (especially in energy) on the Strait of Malacca through new land corridors: (i) the Eurasian rail corridors; (ii) the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor; (iii) gas and oil pipelines (Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline) from several Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan); (iv) gas pipelines from Russia (the Power of Siberia I; the Power of Siberia II (in project)); (v) the East Siberia-Pacific Ocean crude oil pipeline (ESPO); (vi) the trans-Burmese oil and gas pipelines to China (between the Port of Sitwe, Myanmar, and Kunming, Yunnan, China); (vii) a gas pipeline (under project) from Iran, via Pakistan, to Xinjiang, China; (viii) an oil pipeline (under project) from Gwadar, Pakistan, to Xinjiang, China; (ix) the Goureh-Jask pipeline in Iran to the port of Bandar-e-Jask.

The Sunda Strait and Lombok / Makassar Straits

There are at present alternative shipping routes to the Strait of Malacca. The Sunda Strait is more difficult to navigate due to strong tidal flows, with sandbanks, has a minimum depth of only 20 meters in parts of its northeastern end, and there are man-made obstructions, such as oil rigs, off the Java coast. In a nutshell, the Sunda Strait narrowness and shallowness make it unsuitable as a passageway for large, modern ships.

The Lombok / Makassar Straits are more easily navigable yet longer routes, which can increase shipping costs ($84 to $220 billion per year, according to RSIS). The Lombok and Makassar Straits are considered the safest alternative route for supertankers.

To ensure regular use of these Straits, China needs to maintain a good relationship with Indonesia.

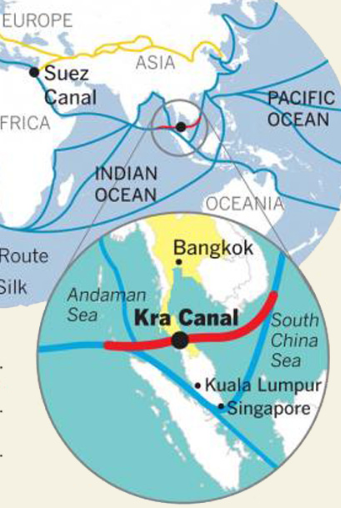

The Kra Canal

The Malacca Dilemma is also at the origin of an ambitious project to create an alternative route between the Pacific Ocean / Gulf of Thailand and the Indian Ocean / Andaman Sea: the Kra Canal (also known as the “Thai Canal” or the “Kra Isthmus Canal”); it has been a project idea since at least 1974, albeit the Thai monarch Narai the Great had already commissioned a study of its viability in 1677. This canal, somewhat similar to those of Suez and Panama, would be made in the Thai part of the Malay Peninsula, with several suggested locations, and would save c. 1200 km and voyage time by 2~5 days on the current sea route between the Far East and Europe, with an estimated bunker savings (for a 100,000 dwt oil tanker) of $350,000 per trip. Bulk shipments (e.g. oil tankers) that are chartered for direct shore to shore voyages will benefit the most. Large container ships that must make frequent stops may not benefit as much – vessel capacity may not be sufficiently utilized when skipping ports in Southeast Asia. Thailand may greatly benefit from the canal toll fees (the cost of using the Canal would be a key factor, though), port facility charges and development in the surrounding area, with the creation of relevant logistics and port hubs, which would cannibalize part of Singapore’s current business in these sectors.

It would also reduce exposure to piracy in the Strait of Malacca. And it would make more difficult to impose a naval blockade of the Strait of Malacca, especially if there are Chinese military naval bases in the Coco Islands (in the Andaman Sea) and in the port of Kyaukpyu, as is likely to happen, in time, following agreements between Myanmar and the PR of China. Anyway, with traffic volumes projected to exceed the Malacca Strait’s capacity by 2030, this new project would provide an alternative to ensure a seamless flow of goods. In 2014, Thailand set up a Thai-Chinese Strategic Research Center (TCRC) [of National Research Council of Thailand] to study the strategic docking and regional cooperation between Thailand and China. The TCRC increased the exchange and cooperation with China, mainly via the National Academy of Development and Strategy of the Renmin University of China (NADS), along with the planning of the “One Belt One Road” Research Center of the China-Thailand Joint Venture and other think tanks of Thailand and China. In May 2015, a Memorandum of Understanding between China and Thailand on the Kra Canal was signed. The Thai-Chinese Cultural and Economic Association (TCCEA) and Thai Canal Association for Study and Development (TCASD), have both suggested that China could finance the Kra Canal as part of one of the BRI’s six designated corridors, the “China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor”. China seemed keen to invest in regional infrastructure projects such as the Kra Canal as part of its BRI. And the P. Chan-o-cha Thai government had promulgated a two-decade national development strategy which emphasized the importance of global connectivity initiatives. But the Kra Canal project did not move forward due to its high cost, opposition in Thailand to dependence of China and the canal being run by China or Chinese companies, internal political disputes in Thailand, environmental concerns and pressure from other countries (US, India and Singapore).

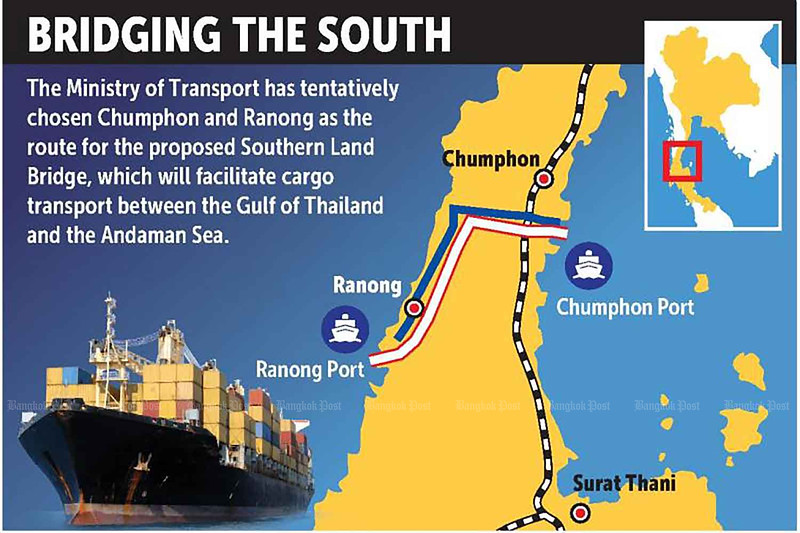

The Thai Land Bridge

Following years of internal debate, the concept of a navigable channel linking the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea was dismissed by the Thai government in 2020. The dream of a Kra Canal was replaced by a Thai Land Bridge, with two deep-sea ports [to be built] in Chumphon and Ranong, linked by road, rail, and pipelines (100 km) to connect the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea, and located well north of the projects for the Kra Canal. This land-based route would avoid major drawbacks involved in digging a canal, such as environmental waste, and, if made more to the north of the Peninsula (as planned now), reduces the insurgency and unrest risks of the [predominantly Muslim] southernmost provinces of Thailand. The Thai government estimated cost of this Land Bridge – 1 trillion baht ($29 billion) – is roughly ½ of the staggering $55 billion projected to be required to make the Kra Canal. The deep-sea ports in Ranong in the Andaman Sea and Chumphon in the Gulf of Thailand may cost 630 billion baht, according to the Thai Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning. Foreign investors will be allowed to own more than 50% in joint ventures with local companies in building the ports and related infrastructure. A 50-year concession will be granted to the winning consortium that may comprise shippers, logistics operators, port managers, property developers and industrial investors. According to the Thai government, this Thai Land Bridge project will help create 280,000 jobs and propel Thailand’s annual GDP growth rate to 5.5% when it is fully implemented (2.6% in 2022). If a feasibility study currently underway is given the green light, Thailand plans to hold an international competitive bidding in the second quarter of 2025 and work could start in 2030.

The Thai government is pitching this mega infrastructure project to global investors, having already made road show presentations to investors in China, Saudi Arabia, Japan USA and Germany.

China has not yet commented on this land bridge project, appearing to prefer a navigable canal. Probably because the land bridge does not solve the problem of large oil and gas tankers (and possibly large vessels carrying other commodities), whose ships would still have to pass through the Strait of Malacca. Nonetheless, Thai officials say the Chinese construction giant China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC) expressed interest in the Land Bridge project.

Despite these initiatives (new land corridors, Kra Canal / Thai Land Bridge), China’s international trade’s dependence on shipping remains very high, which is why the Chinese authorities have been looking for alternative sea routes to and from China – routes via the Pacific Ocean / Panama Canal and Arctic routes.

The transpacific route via the Panama Canal

One of the alternative maritime commerce routes [between the Far East and Europe] is the transpacific route that crosses the Pacific Ocean and the Panama Canal. With the widening of the Panama Canal in 2016, it became possible for Neopanamax container ships to carry up to 14000 TEU (previously, Panamax freighters were limited to 5000 TEU), which is leading some ship owners to consider a route between the Far East and Europe via the Panama Canal via Neopanamax or post-Panamax Plus vessels. And a new widening of the channel is already planned to allow the passage of container ships with a capacity of up to 20,000 TEU.

72.5% of the total traffic that flows through the Panama Canal either begins or ends in the US; China cargo volume accounts for 22.1%, Japan, 14.7%, South Korea 10.1%. Currently, a large proportion of seaborne trade flows from Asia to the US.

Some analysts have argued that the transpacific sea route to Europe still isn’t competitive. But it is a route of great strategic importance for China. It has the advantage that its foreign trade is not dependent on so many exogenous factors beyond its control. Of course, although the Panama Canal is now operated and managed by a Panama Canal Authority (an agency of the government of Panama), its access could also be limited by a naval blockade. But it is far from the coast of China and it is less likely that a naval blockade would be made there; however, in the Treaty transferring the control over the Canal, the US reserved the right to exert military force in defense of the Panama Canal “against any threat to its neutrality”. The potential of this route depends on the ease with which merchant ships to and from China can use the various shipping channels between the Chinese coast and the Pacific Ocean. This is one of the reasons for China’s diplomatic strides with Pacific Ocean countries.

The interest of China in the Panama Canal seems clear. In consonance with the BRI (of which Panama was the first Latin American country to join in 2018), Chinese companies have been involved in infrastructure-related contracts in and around the Canal in Panama’s logistics, electricity, and construction sectors. Chinese companies are positioned at either end of the Panama Canal through port concession agreements. Hutchison Ports PPC, a subsidiary of Hong Kong–based CK Hutchison Holdings is the operator of the Balboa and Cristobal ports, two major hubs of the Canal’s Pacific and Atlantic outlets, respectively. In 2016, in a $900 million deal, the China-based Landbridge Group acquired control of Margarita Island, Panama’s largest port on the Atlantic side and in the Colón Free Trade Zone, a very large free trade zone. The deal established the Panama-Colón Container Port (PCCP) as a deep-water port for megaships, and the construction and expansion were carried out by the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) and the CHEC.

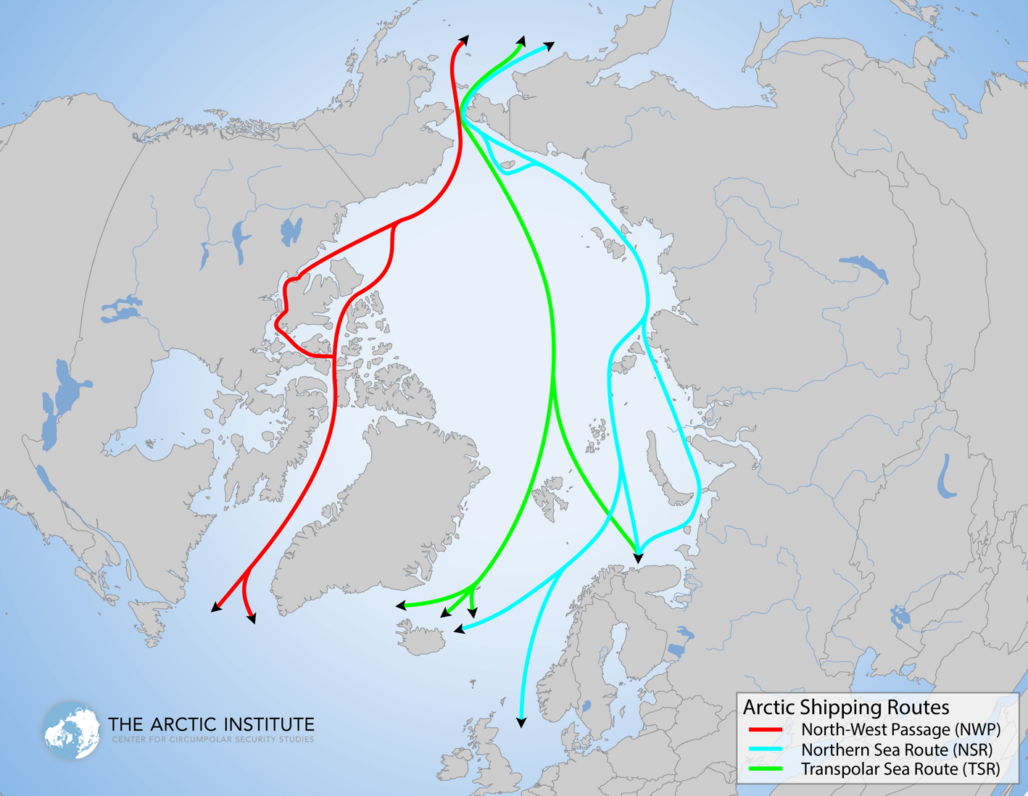

The Arctic routes

Other alternative sea routes for merchant ships between the Far East and Europe are the Arctic routes (also called Northern Sea Routes – NSR). One of them is Canada’s “Northwest Passage”, but it still has several shortcomings in terms of logistics support along the route in Canada’s shipping channels. The main NSR runs along Russian waters in the Arctic Ocean. One advantage of the NSR is that they can significantly reduce travel time between the Far East and Europe. The sailing distance by the NSR from a Northwest European port to the Far East is approximately 40% shorter compared to the Suez Canal route. A container ship from China or South Korea can take about 34-40 days to reach Rotterdam, the main European port. In contrast, on the NSR ships can take around 23 days.

Several years ago, China COSCO Shipping Corp and Maersk have completed voyages testing these Arctic shipping lanes, where gradual melting of ice is expected to allow the route to operate all year-round on a regular basis; currently it operates only during the “navigation season”. Russian authorities believe this NSR could be viable for regular all year-round navigation by 2035. In 2023, Russia’s largest LNG producer Novatek shipped a total of 31 LNG cargoes, or 2.27 million tons, from Yamal Arctic LNG terminal to Asia (including China), during navigation season. Ice-class tankers, methane tankers with a reinforced hull like an icebreaker and able to cut through 2-metre thick ice, are being built at Russia’s Zvezda shipyard, at Guangzhou Shipyard International Co. Ltd (since 2018) and at Hanwha Ocean Co. (S. Korea).

The Arctic Routes will be more likely operated the sooner the Arctic Ocean ice melts due to global warming. Several scientific studies confirm that the Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the world. Apparently, this accelerated warming of the Arctic, with a higher incidence above the Arctic Circle, is essentially due to physical processes, and is melting large areas hitherto covered by ice, including the permafrost. The navigability of the Arctic Ocean will make Russia unavoidable in international maritime trade for decades. From 2035-2040 on, a significant percentage of the maritime trade currently going through the Strait of Malacca and the Suez Canal will be diverted to the NSR, thus significantly reducing the risk underlying the Malacca Dilemma. It is therefore not surprising that Russia and China have agreed to jointly develop the NSR, calling it the “Polar Silk Road”.

Conclusion

China’s leadership and Chinese strategists continue to perceive the Malacca Dilemma as a relevant economic security threat to China. The Malacca Dilemma works also as a strong deterrent to South China Sea serious security or defense conflicts. The protection of its maritime interests has become and will remain a paramount concern of the P R China. This geopolitical challenge will continue to be an important driver of China’s medium- and long-term strategies and international relations. To reduce exposure to the Strait of Malacca, new economic corridors and maritime routes will continue to be opened by Beijing, under its economic diplomacy. The BRI is one of China’s most relevant tools to this end. However, despite China’s attempts at diversification, it will continue to remain dependent on the Strait of Malacca in the short-term. In any case, China’s engagement with several other countries inevitably will continue, in a mutual advantageous economic interdependence.