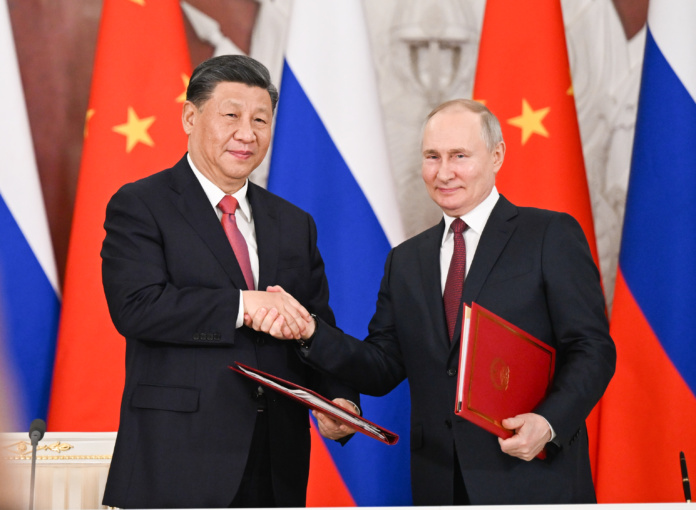

The “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination for A New Era” between Russia and China, concluded in 2019, was re-affirmed during a bilateral summit in Beijing on February 4, that strengthened relations between the two countries, with a lengthy statement then issued saying that “the friendship between the two states has no limits”, “there being no ‘prohibited’ areas of cooperation”. On 20 March, another meeting between the leaders of the two countries took place in Moscow; the two major powers have described Xi’s three-day trip as an opportunity to deepen their “no-limits friendship.”

China and Russia share a long common border and have a long relationship that has experienced different phases from the 16th century up to the USSR-Soviet period and more recently during the Russian Federation and the P. R. of China. At the political level, both countries are founding members of the Shanghai Organization and founding members of the BRICS.

Both countries share a similar vision of combating the hegemony of the US in international affairs, a mutual distrust of the West and disdain for the liberal democratic regimes. China looks for Russia as a partner in standing up to what both see as U.S. aggression, domination of global affairs and unfair punishment for their human rights records. Recent Western trade wars against China, tech export restrictions and the threat of sanctions over Ukraine also conspire to push Beijing and Moscow closer together. Last, but not the least, both countries have a long tradition of non-democratic regimes.

Thus, given its great geostrategic importance for China, this relationship of enhanced friendship between China and Russia should not come as a great surprise.

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it has become clear that most of the world’s governments condemn attempts to alter political boundaries by armed force – a principle reiterated in China’s recent 12-point document on peace for Ukraine. The Chinese economy relies heavily on international trade – about 1/3 of the relevant Chinese companies are exporters – and this war is creating economic instability that has repercussions on the demand for Chinese goods. And, although Ukraine is also a major producer of cereals, food products and raw materials, Russia is a superpower of agri-foods, energy products and critical metals.

The strong and growing anti-Russian sentiment in Europe should be a cause of concern for China, increasingly seen by Europeans as Russia’s de facto ally. Chinese companies’ access to the European market, whether for trade, technology, finance, or other purposes, could be severely affected. This is especially relevant with regard to access to high technology; if the EU follows the US stance on high-tech, many Chinese companies will be left out of these value chains and this will significantly delay their advancement in several cutting-edge technological areas. On the other hand, China continues to need foreign capital and the Ukraine war and financial sanctions imposed by the West have slowed these flows temporarily after the Russian invasion. The West, especially the US, has here a financial Sword of Damocles that China’s leaders are well aware of.

This war has also brought enormous uncertainty to one of the most important projects launched by China, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), especially with regard to the main land corridor of the BRI, reducing investments along the main sub-corridors to Europe, via Russia and Ukraine, and leading to the strengthening of the sub-corridor that crosses Turkey.

However, Russia provides the main viable alternative, in the long term, to the present sea route from the Far East to Europe – of enormous importance to China, which can be blackmailed through maritime blockades by the American naval superpower – through the Arctic Route (NSR).

Russia’s weakness emerging from this war and its dependence on China also opens up opportunities for Beijing to expand its influence in Central Asia. In the new Great Game in Central Asia, it is in China’s interest that its growing influence (mainly economic) in the ‘Stans’ be done without creating tensions with Russia that considers this region as part of its sphere of influence.

It is against this historical backdrop that one should look at China’s 12-point document “on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis” as a contribute for the opening of peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine. On the one hand, China benefits from Russia’s weakening to ensure security on the supply of gas, oil, copper, nickel, platinum, palladium and various other critical and precious metals. The weaker Russia is, the more China companies leverage increases, whether in the access to raw materials and cereals (at discounted prices) or in the entry of Chinese companies into the equity of Russian conglomerates. Russia’s growing economic dependence on China also allows Chinese access to resources that the Russian Government had pre-allocated to other countries; this is clearly the case with gas from the Yamal gas fields, the main destination of which was Europe and henceforth will be China; but it is also the case with the exploration of rich gas fields in the far northeast of Siberia, which were reserved to be concessioned to partnerships with Japanese companies and are now likely to be concessioned to partnerships with Chinese companies.

Nonetheless, China is not at all interested in a half-destroyed Russia, for reasons symmetrical to those of the US. And the very recent long phone call between the presidents of China and Ukraine signaled that Beijing is willing to play a more active role as a mediator in the current war on Ukraine.

Ukrainian leaders need someone on whom Putin depends to force him to stop the war and to open peace negotiations. That is why they consider the Chinese proposal useful. Even acknowledging the significant vested interests of China on Russia and realizing that Chinese pressure on Russia is gradual and that it is still far from its peak.