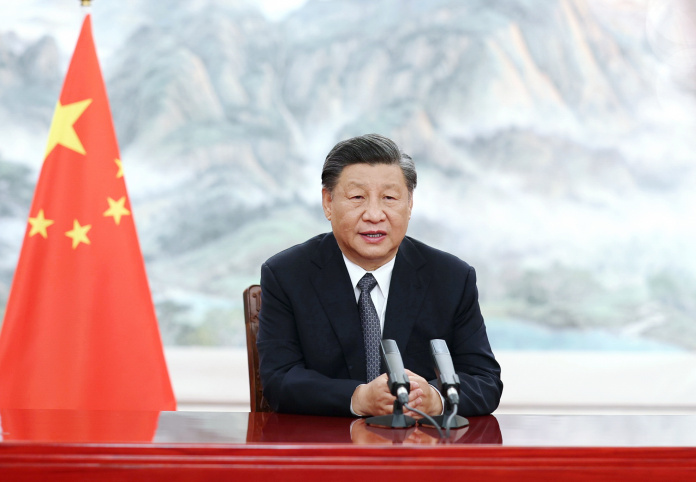

As President Xi Jinping prepares for an unprecedented third term at the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party this October 16, the focus will shift to the challenges the Chinese leader will face in the next 5 years, or possibly more, he is expected to lead the nation.

As the 2,300 delegates gather at Tiananmen Square’s Great Hall of the People for about a week, the orders of the day will provide considerable food for thought

Xi is expected to maintain its first two titles, party General Secretary and Central Military Commission chairman at the party congress – which takes place every five years – and the presidency at the annual National People’s Congress in Spring 2023.

Citing the uncle of the world’s most famous arachnid hero, ‘with great power comes great responsibility’ as 1.4 billion Chinese residents will await some respite to their daily lives woes.

The Covid-19 conundrum

The strict control imposed by Chinese authorities to maintain Covid-19 and its multiple variants has weighed heavy over the country’s 老百性 or ‘common people’.

China’s economy contracted sharply in the second quarter of this year as widespread coronavirus lockdowns hit businesses and consumers, with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) falling by 2.6 per cent.

On a year-on-year basis, the world’s second-largest economy expanded by only 0.4 per cent in the April-June quarter.

Growth in the country also fell to 2.5 percent in the first half of 2022, less than half the ruling Communist Party’s 5.5 percent annual target.

Demand for Chinese exports softened as economic activity in Western markets slowed and the Federal Reserve and central banks in Europe and Asia raised interest rates to cool surging inflation, while imports followed the same downward trend.

Consumer spending and confidence also remained low, with total household spending contracting by 2.4 percent year-on-year, and with Chinese consumers remaining cautious about spending on non-essential items and increasing their savings in the face of growing uncertainty about the economy.

At the same time, China’s official consumer price index (CPI) reached its highest point in two years, rising by 2.5 percent y-o-y in June, with inflation in consumer prices to continue climbing moderately in the coming months.

The International Monetary Fund on Tuesday cut its 2022 and 2023 economic growth forecasts for China to 3.2 per cent and 4.4 per cent, respectively, saying the frequent lockdowns under the country’s zero-COVID policy have taken a toll on its economy

On the border of the rare stagflation witnessed in plenty of world economies as the Ukraine/Russia war continues to wreak havoc, either in investors’ confidence or in costs associated with higher energy prices.

To add to the worries, a property crisis moved by slumping apartment sales and a rash of debt defaults by developers has led to a financial crunch at the local government level.

President Xi and his new entourage will have their work cut out for them, as they look to reinstate confidence in a decelerating economy that witnessed its lowest growth levels since the start of its meteoric rise in the 2000s.

The silver lining rests in the fact that much of the country’s woes have so far been self-imposed by its strict ‘zero-policy’ approach to the novel coronavirus, and easing or outright removing current border restrictions to the country and moving away from flash citywide lockdowns is expected to bring almost immediate respite to Chinese businesses.

As the Asia-Pacific nation maintains this stern approach, bringing the country in step with the return to normalcy advanced by other nations is a crucial advancement by President Xi.

New year, new Premier

The congress will also see about 200 of the National Congress to be selected to join the party’s central committee, together with 170 alternate members, while the central committee will elect 25 people to the party’s Politburo, which will, in turn, appoint the members of the Politburo standing committee.

A renewal in the new concentric levels of power in the country is expected and predicting what new faces will surface on October 16 is famously arduous and challenging for China watchers.

Still, expect plenty of “entrails–reading’ and predictions to be launched left and right in the days to come.

Without wanting to add much to the prediction game, one of the most certain changes is expected to be Premier Li Keqiang.

Li – who turned 67 this year – has been an official face and leader of economic implementation in his role as premier and the head of the State Council, China’s top executive body.

The unwritten “seven up and eight down” rule that those aged 68 retire while those as old as 67 could be promoted, but plenty of long-standing conventions have already been placed aside by President Xi.

A Premier since 2013, Li has been vocal in raising economic concerns over the current covid policy direction he did not depart publicly from the zero-covid strategy.

Although he has not publicly contested this approach, the comments have been seen by some analysts as undermining the country’s top-down guidelines.

The Premier spent a considerable time telling local authorities to increase their support for market players, ease travel restrictions, and step up economy-boosting construction projects.

He has also pushed forward with tax cuts and fees for businesses in opposition to the consumption voucher situs policies advanced in the country’s two Special Administrative Regions.

Li said in March that this year marks his last as premier but could remain a standing committee member.

So far four contenders have been cited as possible replacements for Li, namely, Standing Committee members, Han Zheng and Wang Yang, or Politburo members Hu Chunhua and Liu He.

Each of them has previously served as vice-premier, a prerequisite to ascending to premier since China’s first one, Zhou Enlai.

At 70 years of age, Liu would certainly be a rare appointment, even as a respected and consensual among the party system and to the common Chinese citizen.

Therefore, all eyes will be focused on whom Xi will choose as Li’s replacement as it would signal either continuity of the current economic approach or a possible shift in policy.

A dangerous world

The world President Xi will face in his new term is probably the most dangerous and unstable he has faced since first appointed in 2012.

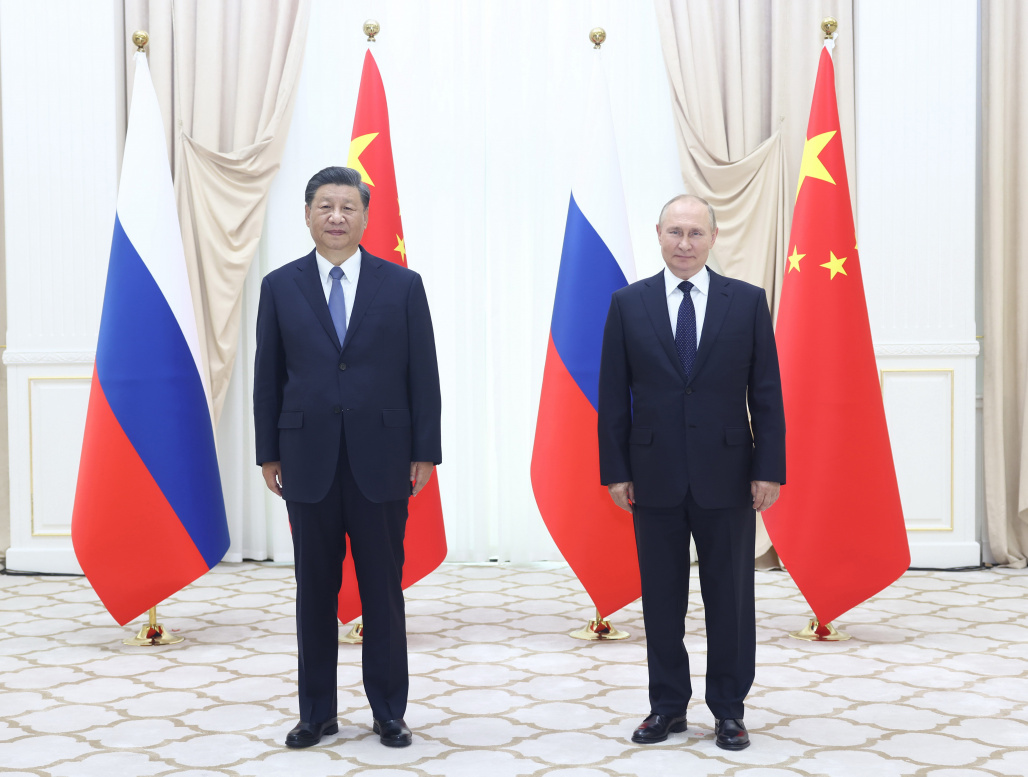

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has thrown a monkey wrench to the shy recovery the world’s economy was undergoing post-covid and forced the country to play an uncomfortable middle-of-the-road approach to the crisis, on the one hand avoiding outright condemnation of what it considers to be a crucial ally in balancing US power, while repeatedly making appeals for de-escalation and peace.

Having a fraught, tense, and hostile world order is of interest to no one, much less the current Chinese leadership, and hopefully, President Xi will play a crucial role in bringing the hostilities to an end. His word is certainly one of the few that a certain Kremlin resident still gives weight to.

Both leaders traveled to Uzbekistan for meetings of the Beijing-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), with Putin himself revealing that Xi had “questions and concerns” over Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

Playing a crucial role in bringing peace to Europe will certainly do much to improve Chinese relations with the continent.

However regained hostility by Western powers on sensitive matters such as Taiwan, Hong Kong or trade could move Xi to make a cost assessment calculation that maintaining the tightrope approach is the most beneficial to the country.

Legitimacy

The large Xi-shaped elephant in the room will be the third leadership term, which ripped up a long-held convention that Chinese leaders serve only two.

To a country whose leadership historically praised continuity and stability, the constitutional changes that made possible this third term are unequivocally a departure from the conventions put in place by the father of modern China, Deng Xiaoping.

Deng – who knew much about the risks of excessive power bestowed to single leaders – placed the term limits in the 1980s as part of his effort to ensure that China’s leaders would not stay indefinitely in power.

Since Jiang Zemin, the president and general secretary are one and the same, but with Xi serving a 3rd term as president, he will likely be invited to stay on as general secretary beyond the age limit of 68.

This unprecedented third term will pose a new challenge to President Xi so far that it places him in a position to justify this departure from the norm.

China’s leadership has so far operated in a system that ensures a rotation of officials in leadership positions with each new president, which assured a reformist impetus.

Maintaining that impetus will now be a new challenge to President Xi, as many will be looking up to assess if personal ties to the President or actual governance competence will be most valued in the years to come.

It will certainly be a new era for China and the world, with President Xi’s governance surely having a deep impact on either one.

[MNA Contributing Editor]