By Jorge Costa Oliveira

Partner and CEO of JCO Consultancy

As the war on Ukraine raged on, China re-affirmed its “neutrality”, albeit adopting a de facto stance of “collaborative [pro-Russian] neutrality” towards Russia. The reasons for this stance are evident – China has much to gain and little to lose from it. Thus, until recently, it was arguable whether China was interested in a quick end to the Ukraine war. In fact, it looked as if it was interested in its continuity (as the US, although for different reasons). Trade between Russia and China grew tremendously after the beginning of the war (Feb 2022) having reached in 2023 a record number of 240 billion US dollars (the number gets much higher if one adds the increase in indirect trade, via Central Asia).

On the other hand, the progressive isolation from Western markets is making Russia and its companies dependent on Chinese firms or China’s authorities. Russia sells (often at discount prices) oil, natural gas, critical metals, agrifoods to Chinese companies, and buys from China cars, machinery and critical components for its defense industry (e.g., drone and missile engines, semiconductors). The growing interdependence between the two countries has provided good business deals for Chinese companies (the top six foreign car brands sold in Russia are now all Chinese, Xiaomi and Tecno have eclipsed Apple and Samsung, the same in home appliances and other everyday items). This dependence has even led to Russian strategic companies relocating to China part of the value chain of relevant products, such as the Norilsk Nickel smelters. In recent months, Russia is boosting China’s military capability by providing Beijing with advanced aerospace technology, as well as advanced air defense systems and technology used in China’s new silent submarines. It is true that, within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and other agreements, Moscow and Beijing already had a good cooperation in the areas of security and defense. However, only in recent months has Russia made advanced military and aerospace technology available.

On the other hand, China maintains a good relationship with many Western countries (mostly European) whose rich markets are the destination of a sizable part of China’s exports and from which advanced technology and investment comes to China. China clearly intends to maintain this situation, as well as avoid financial sanctions that have been imposed on Russia.

Whilst combating an international order dominated by the main Western powers remains the long-term goal of China, an openly confrontational path with the West – as Russia did – is dangerous and entails significant costs, especially in terms of financial sanctions. China stance thus far shows its leadership fully understands this, yet does not want Russia to become too weak from the war effort.

However, the recent escalation of the war effort on both the Russian and the Ukrainian sides, the increased pro-Ukrainian commitment of Western countries, in particular the European ones, and the non-veiled threats by the US governments as regards the supply to Russia of dual use goods, seem to have provoked a change in the Chinese stance as regards the continuity of the war.

It is not in China’s interest to have Russia significantly weakened. However, the war has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Russians, the replacement of military capability is severely jeopardized and the economy of Russia is being transformed into a war economy with progressive allocation of resources for military and defense purposes. Furthermore, on top of the American pressure for Europe to decouple from China (thus far unsuccessfully), several opinion polls show that the image of China in Europe is being eroded at a fast pace. That is creating already significant hurdles and difficulties for Chinese companies in Europe. Moreover, China’s international image is also being damaged, and the dominance of Western media and entertainment globally does not bode well for China’s willingness to reinforce its soft power with developing countries, including as a potential peacemaker of international conflicts.

The Russian leadership, behind the mask of a hardline speech, seems to be aware of its country’s growing fragility. And both the Russian leadership and elites are fearful of this situation of growing dependence from and reliance on China. It is not surprising that Putin keeps reiterating his readiness for a peace agreement in Ukraine. Moreover, the timing for peace talks is good for Russia given the current military situation on the battle fields.

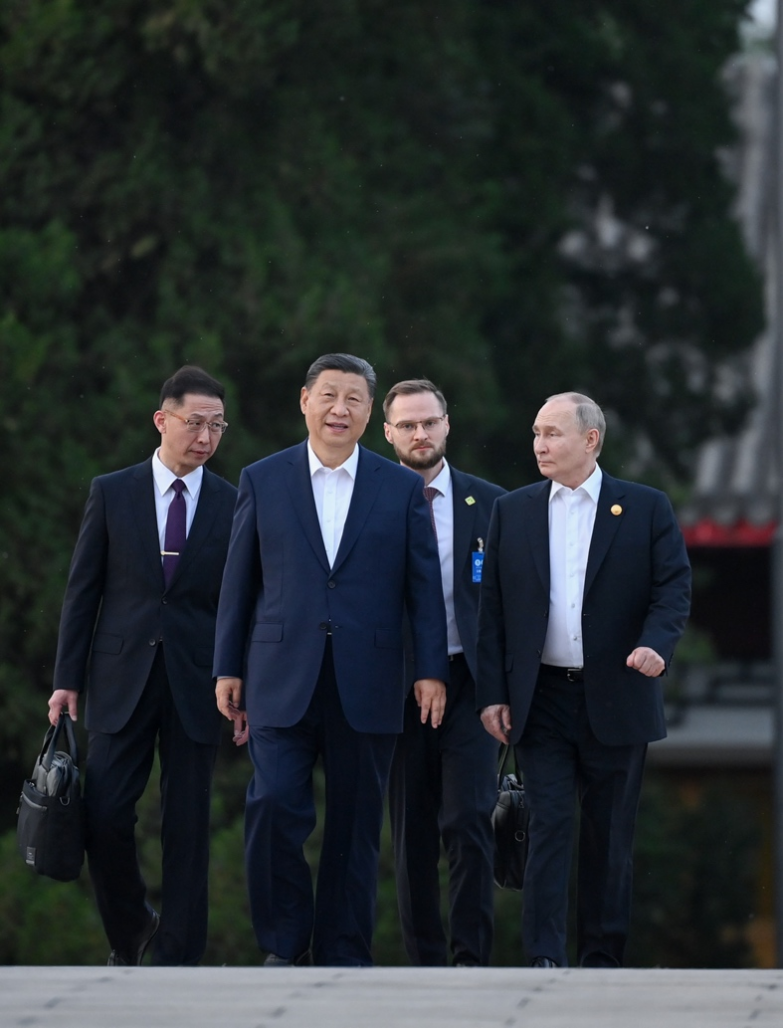

The Beijing leadership, although certainly pleased by Russia’s growing reliance on China, seems to have brought into the equation other relevant concerns of China. It is in this light that the statements made by Chinese officials before and on the occasion of the 16-17 May visit to Beijing by the “lao pengyou” (old friend) Putin should be analyzed.

A month before the visit, Feng Yujun – one of China’s leading Russia experts and a professor at Beijing University’s School of International Studies – published in The Economist an article whose title is: “Russia is sure to lose in Ukraine”. It is hardly credible that such an article in a high profile international magazine was published without the express consent of the Chinese authorities, rather it is likely that it was written upon request. Feng Yujun lists 4 reasons why he thinks the Russian Federation will lose to Ukraine: (i) the extraordinary level of resistance and national unity shown by Ukrainians; (ii) the international support for Ukraine, which, though recently falling short of the country’s expectations, remains broad; (iii) the nature of modern warfare, a contest that turns on a combination of industrial might and command, control, communications and intelligence systems; (iv) information as a key factor in decision-making; Putin and his national-security team lack access to accurate intelligence and the system they operate lacks an efficient mechanism for correcting errors, while their Ukrainian counterparts are more flexible and effective. Prof. Feng’s conclusions are also very interesting: (i) Russia will be forced to withdraw from all occupied Ukrainian territories, including Crimea; (ii) Russia’s nuclear capability is no guarantee of success (he gives the example of the US, which left Vietnam, Korea, and Afghanistan with no less nuclear potential); (iii) Kyiv has proven that Moscow is not invincible, so a Korean-type armistice is ruled out; (iv) the war is a turning-point for Russia; it has consigned Putin’s regime to broad international isolation and forced it to deal with difficult domestic political undercurrents – from the rebellion of the Wagner Group to other pockets of the military to ethnic tensions in several Russian regions and the recent terrorist attack in Moscow; all these show that political risk in Russia is very high; (v) after the war, Ukraine will have the chance to join both the EU and NATO, while Russia will be further away from the former Soviet republics because they see Putin’s aggression in Ukraine as a threat to their sovereignty and territorial integrity; (vi) the war has made Europe wake up to the enormous threat that Russia’s military aggression poses to the continent’s security and the international order, bringing post-cold-war EU-Russia détente to an end.

As Prof. Feng points out, the war has highlighted that “China and Russia are very different countries” with increasingly differing objectives in their foreign affairs. “Russia is seeking to subvert the existing international and regional order by means of war,” he writes. “Whereas China wants to resolve disputes peacefully” and without exacerbating the current tensions between China and the West. In the words of Prof. Feng Yujun, “shrewd observers note that China’s stance towards Russia has reverted from the ‘no limits’ stance of early 2022, before the war, to the traditional principles of ‘non-alignment, non-confrontation and non-targeting of third parties’”. And he adds that “no one should doubt China’s desire to end this cruel war through negotiations.” This wish, Prof. Feng says, “shows that China and Russia are very different countries. Russia is seeking to subvert the existing international and regional order by means of war, whereas China wants to resolve disputes peacefully.”

Putin’s recent visit to Beijing was a way for the leaders of China and Russia to show a united front and reiterate their “comprehensive strategic partnership”. Nonetheless, it is especially important to pay attention to a “restrictive meeting” of Xi and Putin in Zhongnanhai (the new Forbidden City, in Beijing), “during which they had in-depth exchanges on strategic issues of common concern”, as written in a statement by China’s state agency Xinhua, posted on the Chinese government’s website. In this “restrictive meeting”, Xinhua reported, “Xi said China supports the convening of an international peace conference recognized by Russia and Ukraine at an appropriate time with equal participation and fair discussion of all options, so as to push for an early political settlement of the Ukraine issue” and that “China stands ready to continue to play a constructive role in this regard.”

The warnings in Prof. Feng Yujun’s article, and the demand for “an early political settlement of the Ukraine issue” constitute an evolution of China’s stance. Europe should use this window of opportunity to join efforts with China to actively promote a ceasefire and realistic peace negotiations, i.e., with both sides at the table.