Since the Han dynasty, over the centuries and dynasties, Confucianism – transformed into a bureaucratic ideology to serve the interests of the Middle Kingdom – constantly reinvented itself, accommodating to the dominant philosophical and political orientations of the time (e.g., during the Song dynasty it integrated elements of the Buddhist and Taoist philosophies that were then sweeping China).

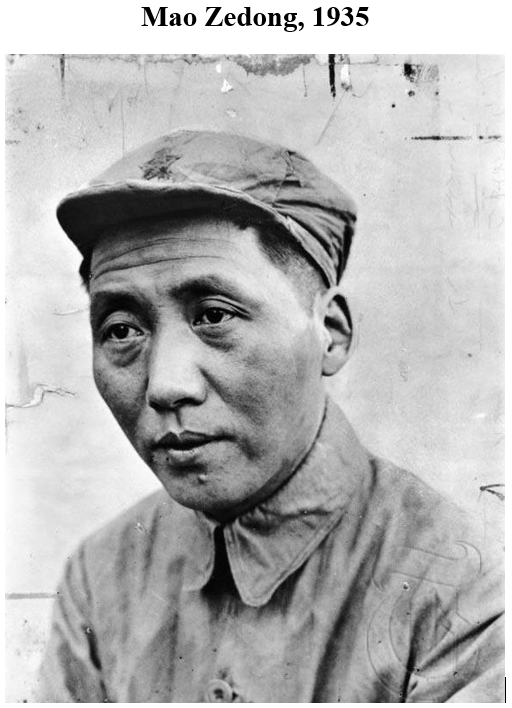

With the establishment of the Republic in 1912, Confucianism lost support – after all, it was the Confucians’ arrogance of resisting modernization and considering modern [Western] knowledge as strange and frivolous that led to China’s backwardness and humiliation before foreign powers. in the 19th century – having been ridiculed and insulted during the “Movement for a New Culture”. When the Kuomintang nationalists came to govern the country in 1927, Confucianism regained some of its lost status. With the creation of P.R. China in 1949, Confucianism became anathema. This was not always the position of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In his speech to the Sixth Plenary Session of the Sixth Central Committee of the CCP in 1938 – which established Mao Zedong’s undisputed pre-eminence – Mao asserted that CCP members should study China’s “historical heritage” and “preserve the precious legacy of Confucius to Sun Yat-sen” to adapt Marxism and Leninism to the specific conditions of China.

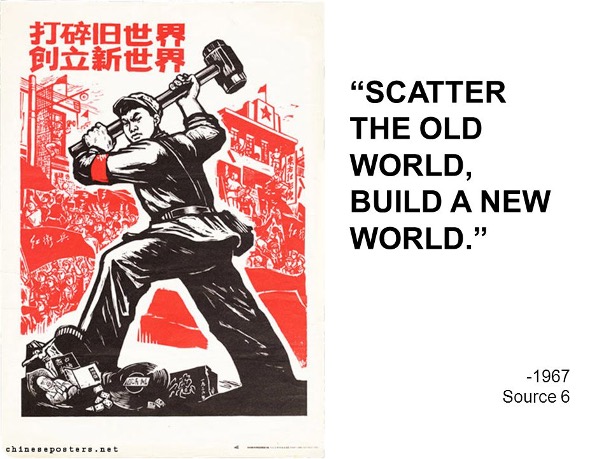

However, after 1949, the CCP considered the Confucian belief system bourgeois and reactionary; Confucius and Mencius “represented slave owners and aristocrats”, so they were considered “enemies of the people”. The “Cultural Revolution” (1966-1976), with Mao’s exhortation to “Crush the Four Old [Things]” – “old ideas”, “old culture”, “old customs”, “old habits” – fought fiercely Confucianism (“Criticize Lin Biao, Criticize Confucius” Campaign of 1974), leading to the destruction of hundreds of temples and the burning of Confucian texts, with “The Analects” being banned.

In the 1980s, it was still so maligned that historian Yu Ying-shih said Confucianism had become a “wandering soul” devoid of an institutional “body.”

With the policy of liberalization and openness to the outside world promoted by Deng Xiaoping, China underwent a social transformation that gradually led to a blooming of ideas that drew heavily from the influence of Western societies, putting the CCP under great pressure for change, including the improvement of the legal system and political reform. With the CCP leadership maintaining a “firm fight against bourgeois liberalization”, the dissatisfaction of various sectors of the Chinese society, starting with university students, to such resistance to change led, in 1989, to successive demonstrations and the Tiananmen square uprising, in Beijing, where the young protesters erected a statue of a “Goddess of Democracy”.

After the Tiananmen massacre and subsequent crackdown, the CCP and several Chinese think tanks desperately sought that blend of philosophy and history that could instill a nationalist sentiment and insulate the Chinese masses, especially the youth, from Western values (democracy, civil liberties) that had influenced the protesters of Tiananmen and enter(ed) China daily through VPNs that allow them to bypass the ‘Great Firewall’.

One thing was certain: no matter how much rhetoric the CCP spells out about its devotion to Marxism-Leninism, party leaders realized long ago that the “construction of a socialist state based on SOE with a[n inefficient] centralized planned economy on the path to communism” would probably lead to a repetition of what happened in the defunct Soviet Union.

With the economic reform and open-door policy initiated by Deng, state capitalism was transformed into a mixed economic system with an increasingly thriving private sector. The success of the option for a singular economic path, along with the shake-up from Tiananmen demonstrations in 1989, showed the need to reinforce the political legitimacy of the party. The option was for a strong nationalist base, anchored in an unquestionable “Chineseness”, christened “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. In a nutshell, the outcome of this reflection was the return of Confucius, by the hand of the CCP.

By promoting the resurgence of Confucianism, the CCP seeks to reconnect with China’s cultural identity, reinforce national pride, and link the party to the preservation of China’s traditional values and historical roots. Furthermore, Confucian teachings place an emphasis on social harmony, ethical behavior and hierarchical order, values conducive to maintaining social stability, especially in a context of rapid modernization and social change. By promoting Confucianism, the CCP reinforces social cohesion and alleviates potential conflicts arising from rapid social transformations. Confucianism’s promotion of personal virtues such as integrity, filial piety, and respect for authorities offers a moral and ethical framework that is in line with the CCP’s discourse of instilling ethical behavior among citizens as a contribution to a more harmonious society and responsible citizenship. Lastly, but of no less importance, by supporting Confucianism, the CCP also increases its political legitimacy, presenting itself as the guardian and interpreter of traditional Chinese values, seeking to align them with its political objectives. And the Confucian idea of centralized authority and respect for political leaders serves the CCP’s interests in governance.

It is therefore not surprising that in the 1990s, the elite began to speak warmly of Confucius and that there was, under the patronage of the State, a flurry of research and conferences about his doctrine. Several Chinese leaders participated in multiple ceremonies and conferences on Confucius and his teachings. Expressions such as “harmonious socialist society”, “harmony despite different points of view”, or “people as the basis of the state”, strongly linked to classical Confucian doctrines, appeared. The first decade of this century saw the creation of the “Confucius Institute” (in 2004) and its rapid international expansion, in one of the first manifestations of China’s external projection and increase of its soft power. The trend was furthermore accentuated with the use of Confucian concepts by CCP leaders; in 2005, Hu Jintao presented the ideal of a “harmonious society” for China, reiterating that “culture is the lifeblood of the nation” and calling for the promotion of “traditional” Chinese culture and making references to the “great revival of the Chinese nation”.

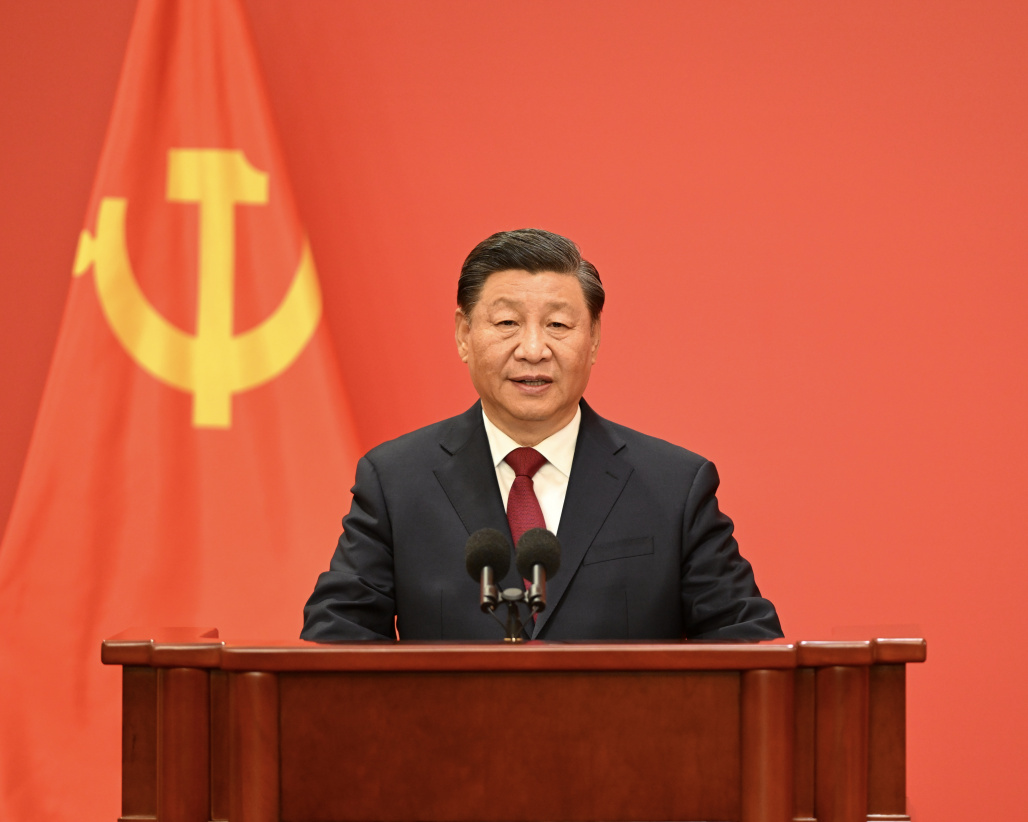

Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, not only has this rehabilitation continued, but Confucianism and legalism have become particularly important in supporting Xi’s dual rhetoric of “rule by virtue” and “rule the nation in accordance with law”. However, the rehabilitation of Confucianism is conditional on it being subordinated to the interests of the CCP. A battalion of “socialist Confucians” studies the adequacy and harmonization of Confucianism with Marxist principles, in accordance with party guidelines. The aim of this “study” of Confucianism is to legitimize the authority of the CCP and thus seek to modify Confucianism “under the positions, principles and methodologies of Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought”. Fang Keli, one of the most prominent socialist Confucianists, argues that Confucianism is complementary to Marxist ideology and can be useful in preventing “Western liberalization” and promoting “the patriotism of the Chinese people.” In short, under Xi, Confucianism serves to reinforce the Sinicization of Marxism, but subordinated to strengthening the party’s legitimacy as holder of the “Mandate of Heaven”.

The CCP leadership continues to feel the need, without losing the Marxist-Leninist roots, to accentuate its Chinese component. In part, this had already happened with “Mao Zedong Thought”, “Deng Xiaoping Thought” and, more recently, “Xi Jinping Thought”. But it is this adapted and functionalized Confucianism that provides it a deep connection to Chinese cultural identity. This alchemy, marked by the tension between the revolutionary and the conservative, the past and the “future”, and by the “fusion of ideologies” between a Chinese version of Marxism-Leninism with traditional Confucian teachings, led the American sinologist Lucian Pye to define the P.R. of China as a “Confucian Leninist State”.

Over time, one will see whether the Chinese wenming (cultural civilization) will continue to be subordinated to Marxism-Leninism… if the ruling elite holding political control of the country will, due to inertia and risk aversion, maintain a Marxist-Leninist[-Maoist-Dengist-Xiist] party or whether gradually convolves it into a party with a proto-Confucian ideology more rooted in Chinese history and culture.